In the United States, roughly sixteen percent of the population lives in multi-generational households. I couldn’t find the statistics for Canada, but I have heard that the numbers are comparable. The financial crisis didn’t hit us as hard here in Canada, but this trend goes back further than that, and I’m not surprised to hear that it’s growing.

In the United States, roughly sixteen percent of the population lives in multi-generational households. I couldn’t find the statistics for Canada, but I have heard that the numbers are comparable. The financial crisis didn’t hit us as hard here in Canada, but this trend goes back further than that, and I’m not surprised to hear that it’s growing.

In 2005 I found myself having to move back in with my mother and stepfather for a while. I’d dropped out of grad school, my partner of seven years had left me for someone else, and I was so broke that not only was I about to lose my apartment, but I’d been suffering from serious depression and malnutrition in no small part because I couldn’t afford to feed myself and was too stupid to visit the food bank (too stupid, not too proud; it didn’t even occur to me). I lived with them for thirteen months in Waterloo (where they had moved while I was in university) while I worked a dead-end job trying to save enough money to move to Toronto. I love my mother and stepfather, and I fell in love with a remarkable woman while I was living there, but I will always remember that period as one of the worst times of my life, if not the worst.

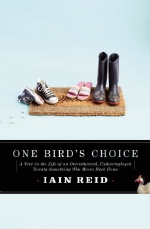

Iain Reid appears to have had a better time of it. For one thing, he got to move back into his childhood home, but he also managed to line up a job at the nearby CBC radio station. One Bird’s Choice is Reid’s chronicle of his first year living back at home, adjusting to the rhythms of the farm and the surreal experience of being an adult, but having to step back into the role of a child.

Reid’s take is generally light-hearted. There’s the funny story about cleaning the barn, the funny story about playing ball hockey with the kids at a local school (one of my favourites), the funny story about breakfast routines. Reid is no David Sedaris, but for the most part his anecdotes are fun, and sometimes even sweet. However there are times when they can feel a bit manic; relentlessly fun, and relentlessly sweet. A lot of tension can build up living in a situation like that—more than people living on the outside would really understand—and while Reid acknowledges that tension (the awkward Christmas dinner followed by Reid’s solitary walk to go skating is the darkest moment in the book, but it’s also the best; it provides a much-needed emotional counterweight to the humour), it feels like he’s taking great pains to downplay it. I’ve met Reid (in fact, he’s the one who sent me the book), and he’s an exceptionally personable guy. There’s a line that memoirs have to straddle, between faithfulness to the truth and the author’s relationship with his subjects. Reid could very well just be the kind of guy who only wants to focus on the lighter things, and while that’s an impulse I can understand, I think the book is weaker for not including more moments like that walk in the dark.

Though it sometimes lacks nuance, I enjoyed One Bird’s Choice, and it’s an optimistic, feel-good kind of take on a subject that can be (as I know from experience) hugely depressing.

One Bird’s Choice was my second selection for the Fourth Canadian Book Challenge.