Some weeks ago I was at the Toronto launch for Robert J. Wiersema’s sort-of memoir, Walk Like A Man. Because I know Rob in the let’s-grab-a-beer kind of way, I was part of the entourage that wound up shuffling with him to some late night diner/bar combo down near The Esplanade, and there I found myself seated next to author Adrienne Kress. Kress, it turns out, is more fun than eight separate monkey barrels, and so I got her to write down the titles of her books so that I could look them up at the library. And look them up I did.

Some weeks ago I was at the Toronto launch for Robert J. Wiersema’s sort-of memoir, Walk Like A Man. Because I know Rob in the let’s-grab-a-beer kind of way, I was part of the entourage that wound up shuffling with him to some late night diner/bar combo down near The Esplanade, and there I found myself seated next to author Adrienne Kress. Kress, it turns out, is more fun than eight separate monkey barrels, and so I got her to write down the titles of her books so that I could look them up at the library. And look them up I did.

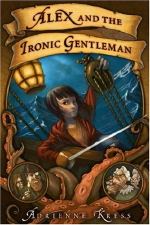

The obvious place for me to start was Alex and the Ironic Gentleman, as it’s her first novel, and, based on the last page of the book, introduces characters that appear in her follow-up, Timothy and the Dragon’s Gate. Now, I don’t generally write about books for young people, not because I don’t read them (though they are a long way from my primary reading material), nor because I don’t enjoy them (I have enjoyed several in the last few years), but rather for the same reason I don’t write about poems and books of poetry: I don’t feel like I read enough of them, or understand them and the culture around them well enough, to offer anything like an informed opinion. I’m making an exception for Alex and the Ironic Gentleman because a) I liked it a lot, and b) I really enjoyed meeting Adrienne Kress, I think that if you can say something good (and genuine and honest and not at all sucking-up) about the cool things someone you’ve met or sort-of-know (ish?) has done, it’s better to say it than not. So anyway.

Alex and the Ironic Gentlemen is about Alexandra Morningside, who is ten-and-a-half years old and lives above her uncle’s doorknob shop. The novel opens as she is entering her sixth year at the Wigpowder-Steele Academy (the names in this book are great). Alex is smart, inquisitive, and capable, and she takes immediately to her new teacher, Mr. Underwood, who apart from being a bit charismatic, really engages with his students and teaches interesting and unusual things. He’s also, it so happens, heir to a pirate fortune. When Alex’s uncle is killed and Mr. Underwood kidnapped by a rival pirate after Underwood’s treasure, Alex embarks on a quest to rescue him, boldly diving into a world reminiscent of Alice in Wonderland (in its quasi-episodic structure, and in Kress’ use of clever, off-kilter almost-archetypes), but more about growing and trying things out in a world that is both modern and anachronistic, that is full of gomi (in the Gibsonian sense, “uncounted strata of message and meaning, age upon age, generated over the centuries to the dictates of some now-all-but-unreadable DNA of commerce and empire”), than it is about standing firm in the face of Opium-trip fantasies as in Carroll’s tales. Kress creates this world through a unique voice that blends British and North American dialects and structures in a way that’s smart, clever (not the same thing!), and often belly-laugh funny.

There’s a lot to be said about the plot, and about the consequences that come from not yet having learned the difference between attractive ideas and good ones, and about different ideas about what it means to be weak or strong (seriously, I could write a ton about the end of this book, but that would be giving things away), but mostly I’m going to focus on two of the peripheral, episodic bits that I quite liked.

First there’s Lord Poppinjay, who runs a hotel in the middle of nowhere, and will be a figure familiar to anyone who’s ever held a job, particularly one in the service industry. He’s lit on the idea that his staff should perform “Mental Dictation” (Kress is quite fond of Capitalizing Important Things, and frankly so am I), ie. they should run his hotel by reading his mind. Alex sorts all this out with a craftier version of declaring the emperor, or in this case, Lord, has no clothes, but at the same time it winds up being a very entertaining send-up of what it can be like entering the work force, or being the boss, or even cooperating in any kind of endeavor where communicating expectations is key. Poppinjay is silly and over the top, but he means well, and the whole episode winds up resonating on so many levels, with implications about how children can experience the adult world, the demands of class, making decisions and dealing with others and blah blah blah there’s just too many things that gobsmacked me with their rightness about Poppinjay and his hotel that there really isn’t time to mention them all. Plus the bits with the fridge were very Douglas Adams.

And then there’s the Daughters of the Founding Fathers’ Preservation Society, which is remarkable in so many ways. The Society consists of a number of elderly ladies who are guardians of the town’s one real historical treasure, the preserved home of Alistair Steele, philanthropist and all around good guy, but ancestor to the greedy folks who wound up causing all the piratical feuding in the first place. The Society figures prominently early on in Alex and the Ironic Gentlemen, as the Steele Estate is home to the treasure map indicating the whereabouts of the Wigpowder treasure, but after that they make only intermittent—but terrifyingly comic—appearances.

You see, there’s this red velvet rope (is it velvet? Kress never says, but it is in my imagination), and Alex steps beyond it. This is a Big Deal. But here’s the thing: you already knew it was a Big Deal. How could you not? Red ropes, velvet or otherwise, are signifiers of status and access and even agency that we learn to recognize at a very young age. They are the kind of archetypal boundaries we push as youngsters and respect with powerful rigidity as we get older. When we’re kids it’s daring to go past one, and generally speaking the worst thing that happens to us is that our parents are told to bring us into line, or we get the boot from wherever we are that needs red ropes. In themselves they are flimsy, completely ineffective obstacles, but they teach us to understand the nature of taboos and symbolic boundaries, and I think it’s fair to say that along with respect, there may even be a few drops of fear attached to them for some of us. After all, as we get older they no longer just separate us from dusty libraries in homes preserved by a local Society, or corral us into the right theatre at the cinema, they also separate us from the wealthy, the famous, and the powerful. The consequences of crossing one of those red ropes without permission could be getting arrested, or even (if, say, Barack Obama were on the other side) getting shot. Red ropes mean serious business.

Alex crosses the rope, obviously, and it’s an act with consequences. There are the silly ones, like the way the Society punishes her by making her hold a mug of water above her head (there is some genuine cruelty in the Society, but Kress’ treatment of them is pitch-perfect in opening that up as an avenue for absurdity), but it’s also a big factor in her quest to rescue Mr. Underwood, and people die in that enterprise (none of that is Alex’s fault, really, but neither is she entirely blameless, and Kress does a really good job of exploring how responsibility and consequence are problems with solutions—our actions and intensions—that aren’t always easy or clear or even clean, and in fact I wish more authors who write for adults would take some time to tease out those issues). There are so many things intertwined with the Society and that red rope. Authority doesn’t separate good people from bad, symbols and boundaries are not absolute, but nor should they be addressed lightly, etc.

Anyway, I’m going on and on about things like growing and learning and all sorts of subtext and whatnot, perhaps a bit more than is proper (I really don’t have a handle on the critical language to deal with books for young people), but I did see a lot of subtext. Alex and the Ironic Gentleman (the Ironic Gentleman is the name of (modern pirate) Steele’s ship, and it turns out to be such a great name, and fans of Patrick O’Brian and other sea stories will find Kress’ attention to nautical detail a pleasant surprise) is rich and dense, but it’s also just super fun. I mean, yes, I found all these wonderful ideas in it that are about childhood and adults and so on, but it’s not like they were wedged in there or even necessarily in there in a conscious way. Kress’ first novel really is, first and foremost, a very entertaining adventure story that gets harder to put down the further into it you get. I’ve already got Timothy and the Dragon’s Gate on hold at the library.