I don’t know if the geeky things I choose to read online on a regular basis just aren’t diverse enough (a strong possibility, given my recent analysis of my 2015 reading list), or if something has happed to cause a number of folks to write about the same or similar issues at more or less the same time, but regardless, people seem to be talking about or around the concept of “hardness” in science fiction. I’m going to throw some links at you, and then we can talk about them. Charlie Stross recently hosted a fascinating discussion on science fiction shibboleths on his blog (along with a similar one about Fantasy shibboleths, which is not relevant to us today, but worth taking a look at in its own right), Charlie Jane Anders put up a great piece about how to integrate character development into your action-oriented story (which is extremely relevant to this issue), and just this morning a post by Fran Wilde went up on Tor.com that cuts right to the heart of the issue, and was the catalyst for this post.

The first thing we should talk about is “what do we mean by ‘hardness’ in science fiction?” Each of the authors surveyed in the Tor.com piece took interesting stabs at answering the question, and I’m going to use the one by Linda Nagata, which I think most accurately sums up what it means in the everyday vernacular of geeks, or at least the geeks I hang out with. So this is what I mean:

[Hard science fiction is] science fiction that extrapolates future technologies while trying to adhere to rules of known or plausible science.

Someone named Random22 also posted a somewhat snarky definition in the comments that, sadly, experience tells me often works just as well.

A good way to define “Hard” SF is to go online and see if someone is using liking it as a way to sneer at people they consider less intelligent than them for not liking it. If they are, then chances are it is hard-SF.

This brings up a bunch of interesting stuff that I want to address later, but keep that in the back of your mind and let it ferment for a while.

Okay, so, when we talk about things like extrapolation and plausibility I hope we all realize that we’re working with a sliding scale, and the thing that causes the slide is the reader.

Suppose we want to write about combat between spaceships, which I hear is something the kids are into these days. Now, I am big fan (a big fan) of historical adventure novels, specifically those written by Patrick O’Brian, sometimes called “the Jane Austin of the sea” because he also does sociological depth, satire, and really solid character work. Anyway, Napoleonic navies duking it out is my jam, so if broadsides in high orbit is how you set up your spaceship combat, while there will probably a little voice in that back of my head that says, well actually (because every buzzkill asshole, including me sometimes, likes to deploy that phrase), it wouldn’t really work that way, that little shitheel voice will never get loud enough to drown out the boatload of fun I’m having, and there will probably be drinks and high-fives all around if I ever run into you at a bar.

Charlie Stross would take your book and throw it across the room in frustration, and he might scowl at you from across the room or something (I’m just kidding about the scowl; I’ve never met him, but he actually comes across as a pretty pleasant fellow online). His scale has a lot more friction to it than mine does. A lot of that is background, you know? As far a science and engineering stuff goes I have high-school-level physics and chemistry, was a pretty able biology student, once worked as the research assistant for the former Canada Research Chair in Biocomplexity doing some stuff on complex system theory, was twice the teaching assistant for an environmental responsibility course for mining engineers, used to teach courses on basic computer usage and how to write HTML/CSS (plus am slowly teaching myself Swift), and have training in how to read and draft blueprints. I am, on my best day, an average-citizen generalist. My speciality training is in English literature with a subspecialty in interdisciplinary humanities/policy analysis. (I only know all that other stuff because I have always believed I would be best-served by a well-rounded body of knowledge.) Mr. Stross, on the other hand, has some pretty hardcore computer science credentials (in terms of achievement as much as formal education), plus serious training in pharmacology. The things that bug me are going to be different from the things that bug Mr. Stross. You know how China Miéville does those italicized pseudo stream of consciousness sections? Yeah, they drive me up the goddamn wall. I’ve got years and years of formal education in techniques like that, having studied a body of literature that literally spans hundreds and sometimes even thousands of years, and I gotta say, he’s really fucking bad at it (and I kind of have thoughts on why, but that’s a digression). Iron Council made me want to throw the book across the room because to me those sections were showy and gimmicky with none of the obvious deliberateness behind it that you find in Sterne or Joyce or Woolf, or hell, even somebody like Coover. Stuff like that is, for me, what Napoleonic navies in space are for Mr. Stross.

The Science Fiction Shibboleths discussion hosted by Mr. Stross often looks, at first glance, like a list of places where writers have failed in their research, failed in their execution, or even failed in their imagination. But it’s not. It’s really just a long accounting of different places where the sliding scale can encounter friction. Luckily for everyone, some of the folks in that thread listed bad character work as their biggest shibboleth. (Is that how you measure shibboleths? By size? Whatever, I’m running with it.) That happens to be my biggest shibboleth as well. Let’s bring Ms. Anders in to talk about that for a minute.

She’s got this great listicle about improving your shorts stories (and, as an aside, can I say how upset I am that my spellcheck accepted “listicle” as a real word?) in which she skewers the concept that there are “plot-based” stories and “character-based” stories. Now, you can have stories where there’s lots of plot and very poorly developed characters (I could pick on somebody like Steve Stanton here, but the really famous example is Lord of the Rings), but with a few exceptions for things like allegories and folk tale forms, we usually just call that bad writing.

It’s really hard to go the other way, though. Nicholson Baker’s novel The Mezzanine might be one of the most amazing things in the history of American letters, and it’s essentially a novel about a guy buying shoelaces and riding an escalator on his lunch break. The reason for this is because, as Ms. Anders points out in the more recent piece—and I’m paraphrasing—is that plot is character. (And though that piece is particular to how to add good character stuff to action stories, you can substitute “science” for “action” or anything else your plot is heavy on and it still works.) Plot is stuff that happens. Stuff happens because people do things, even when “doing things” means making a decision or thinking thoughts. People do things because they have desires (and those desires run the gamut, from “I’m thirsty” to “I don’t want these aliens to destroy the world”). Stuff doesn’t happen without your characters having desires. It just doesn’t. Even The Martian, which I think is by common consensus a hard science fiction book, has its entire plot driven by desire. Here’s how (kind of spoilery, but I feel like the statute of limitations is up on that one): There are people up on Mars because humanity had a desire to explore and expand our collective knowledge. A consequence of that desire is that a bunch of humans got caught up in a really bad storm. These same humans had a desire to not be killed by the storm, therefore they hauled ass to their spaceship and tried to get off Mars. One human got left behind while they were hauling ass through the storm (an action they undertook because their desire to survive had consequences). The bulk of the rest of the book seems like it’s all plot, all process, as Walter Jon Williams would say. But Mark Watney, our human who was left behind, had a desire to continue not dying, and that desire is what drives the process. He solves problems because of that desire. Everything single thing he does during his time alone on Mars is in service to that desire, right down to his decision about when and where to defecate. You might call that a fear rather than a desire, specifically the fear of dying, but fear is just the desire for a negative, the desire to avoid a particular outcome or set of outcomes.

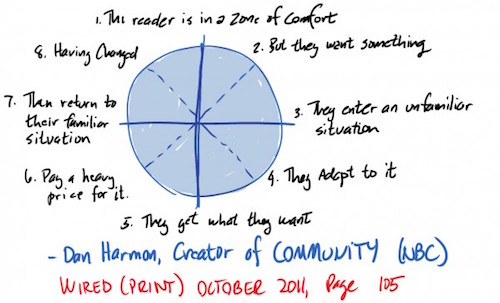

Dan Harmon, creator of Community and co-creator of Rick and Morty has a whole system for putting this together in his stories. He’s not the first one to come up with it, I’ve seen the same thing presented in a bunch of different ways over the years, but I like his and it’s available online. Both of Harmon’s shows are full of wacky, hilarious bullshit, and both shows have some of the deepest, most sophisticated character work on TV (you should also check out You’re the Worst, which has a different flavour but is functionally identical in terms of how this stuff works). Harmon is a problematic figure, but he knows his shit. Here’s the breakdown:

- You (a character is in a zone of comfort)

- Need (but they want something)

- Go (they enter an unfamiliar situation)

- Search (adapt to it)

- Find (find what they wanted)

- Take (pay its price)

- Return (and go back to where they started)

- Change (now capable of change)

Holy shit, you know what I just realized? That’s The Martian! Okay, true story, I didn’t just realize that. But you get where I’m coming from, right? Plot is character: Harmon’s entire story circle, and every rule in Ms. Anders’ second (quite good) listicle, every single one, derives from that first one. It’s truly the one and only inviolable rule of realist fiction writing (in the J. Hillis Miller sense of “realist”).

I’m a fan of a whole bunch of different science fictions. Give me the sociology of le Guin or Leckie. Give me Star Wars and Ex Machina. I fucking loved The Martian; it was big fun, and I want more like it. Give me John Scalzi and Charlie Stross. Give me Phyllis Gotleib and Emily St. John Mandel and Sandra McDonald. William Gibson has been my favourite living author for years, and I’ve recently come to love the work of M. John Harrison and Simon Ings. I don’t really care where your science fiction falls in terms of hard or soft. It’s always going to have a point of friction, and I’m cool with that. However: do not leave your characters behind. I’ve only read one book by Robert J. Sawyer, for instance, and professional interest means I’ll probably read others, but Triggers didn’t work for me because he had his interesting idea, but his action didn’t derive from his characters’ desires, so we wound up with sandpaper-on-genitals levels of friction. I did not believe in a tender love story between a woman who was the recent victim of extended abuse and the guy who could almost literally read her mind, whose earlier impressions of her were pretty focused on her “rack.” I can believe that people become trapped by cycles of abuse and self-destruction and their desires will not always coincide with their best interests, but you can’t make me believe those situations are healthy.

Look here: you know Rob Rinehart, that guy who makes that Soylent meal replacement gunk? Remember that time when he wrote that thing about getting rid of his kitchen? There’s a reason he’s the subject of a fair amount of ridicule from the population at large, and it’s only partly because of the ridiculous name of his product, although the name is a symptom of the same problem. What’s revealed both by that blog post and the product name is a complete and utter contempt for the human experience, a rejection as unnecessary and wasteful a set of cultural touchstones and rituals in which many, even most people find deep meaning and community. His rejection of those touchstones and rituals is in favour of the mechanistic, of process. It is analogous to the rejection of character for plot. He’s like the living embodiment of thinking that getting the orbital mechanics right matters more than character. And you know what? He comes off as creepy as fuck, and your book probably will too if you treat characters like nothing more than counters to move around your plot.

Here’s where we get to that second definition I posted above. Now, normally I’d rather fuck a pile of rocks with a snake in it than approach a topic like this, given the bullshit that’s gone down with sad/rabid puppies and those gamer gater assholes when they’ve thought people were criticizing something they like, but it’s time for some real talk.

There is this thing that runs through geek/fan culture—and it comes from our culture at large, but at this moment it seems to have become amplified and reached a kind of crisis point in geek/fan culture—where some members of the group have decided they need to impose a litmus test before they will acknowledge some other members’ belonging as legitimate. This is some bullshit, and grows out of a strain of contempt and derision that has been under the surface (and sometimes not so under the surface) of geek/fan culture since probably well before I was born. Fiction outside the SF/F umbrella gets labeled “mundane,” women are labeled “fake geek girls,” and on and on and on. A number of the authors polled by Ms. Wilde for Tor.com brought this up as well: “hard” science fiction has very often been used as a bludgeon within the community to try and police whether or not someone belongs. Very often this bludgeon has been wielded against people who didn’t believe the “science” was more important than the “fiction,” and also specifically against women and people of colour, especially when they believed that certain definitions of “science” (particularly those that include sociology and psychology) are more interesting to them and perhaps more relevant to their lived experiences. As Ellen Klages also notes in the Tor.com piece, “hard” can also refer to difficulty, as in “difficult to do or understand.” She points out that classifying something as difficult creates the perception of value, and we can use that classification to deny other things value, to close science fiction off and make it “members only.” Even worse, this can start to feel like an “objective” way to determine who does and doesn’t belong and—spoiler!—it is absolutely no such thing. If you’re excluding people from having awesome fun just because it isn’t exactly the same kind of awesome fun you like to have I’m going to go out on a limb and say that you’re a bad person and you should feel bad.

Labels, and the “hard” label in particular because of its association with a very old-fashioned view of science as logical to the point of infallible, can be used to justify setting up artificial and discriminatory barriers to belonging. This, I think, is where all this talk of sliding scales and definitions and stuff about how to write characters all comes together. So: enjoy your hard science fiction, because it can be awesome! But don’t be a dick about it.

Sorry kids, comments are still closed due to technical difficulties, but feel free to hit me up on Twitter if you’ve got comments.