Normally at the beginning of every year I post a breakdown of all the reading I’d done the previous year. I won’t be doing that this year. I’ll include some recommendations at the end of this post, but I’m having a hard time worrying about how many books I read by certain authors, or books of a certain kind, or whatever categories interest you, or have interested me in the past. Today, I don’t care.

Normally at the beginning of every year I post a breakdown of all the reading I’d done the previous year. I won’t be doing that this year. I’ll include some recommendations at the end of this post, but I’m having a hard time worrying about how many books I read by certain authors, or books of a certain kind, or whatever categories interest you, or have interested me in the past. Today, I don’t care.

2018 was not a good year. I’ve already written about my cat dying, but my mother also passed away in September, following complications from what is generally routine day surgery. I’ve had great difficulty reading, since then. In the four months since my mother died I’ve read seventeen books, which is roughly the count I normally have for December alone. My concentration is shot, my motivation is shot, and my investment in the world around me, while not gone, has been severely curtailed. A lot of what I do these days could be characterized as low-effort distraction seeking. I feel, at all times, in need of a deep and prolonged rest.

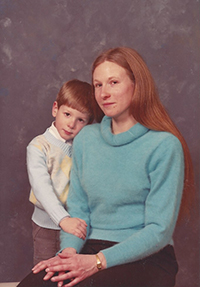

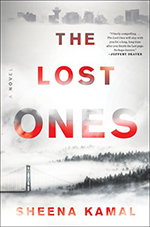

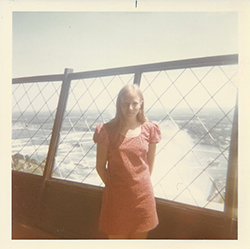

After Molly died I read Julia Cooper’s book The Last Word. Ostensibly about the lost art of the eulogy, it’s more about the role of grief in our society and how we process it, how we are permitted to process it. Huge portions of it made sense to me, but one thing that didn’t was Cooper’s discussion about how long and how severely the loss of her mother affected her as a day-to-day thing. The severity I understood, but not the length. Obviously it’s a loss that isn’t going to go away, I thought, but how could it have such an impact on your day to day life for years? Now I understand, and I wish I hadn’t had to gain that understanding the hard way. So much of what I do has my mother in it, both in the sense of her role in my development as a person, and in terms of what does and does not spark memory. I cried the first time I cooked a meal from scratch after she died. I’ve spent a lot of time being angry at nothing, and I keep having to stop myself from calling her. I can already tell you baseball season is going to be hard this year. She never did get to see a Jays game in person. It’s not clear to me that I’ll be able to read anything by Louise Penny or P.D. James for a long while—my mother and I would swap their books back and forth. She would read one of James’ novels and then pass it on to me, and I would do likewise with Lousie Penny’s. I’d brought my mother a copy of Glass Houses to read during her recovery, which came home with me unread, and now I can’t see it on my shelf or pass it in a bookstore without choking up. The last book she gave to me was Sheena Kamal’s The Lost Ones, which I now doubt I will ever read, but definitely won’t be able to part with. There are a few things of this category in my apartment right now: A beer glass she bought me for Christmas, which is a story in itself of guilt, misunderstanding, and gestures that were appreciated but unnecessary. I ate the last of the ginger candies she gave me on the eve of her surgery, and now there is some kind of pepper sauce I haven’t opened yet, the last gift of food from a mother whose identity was so wrapped up in cooking and eating that it seemed like there would be a never ending flow of it. In my freezer is a Thanksgiving dinner from 2017 that I never got around to eating and is now the last meal she cooked that still exists, beyond eating for age regardless of sentimentality, but that I can’t bring myself to get rid of yet, even though I know I already should have done so. Perhaps not the final gifts from a mother to her son, but the last tangible ones, from her hand to mine.

After Molly died I read Julia Cooper’s book The Last Word. Ostensibly about the lost art of the eulogy, it’s more about the role of grief in our society and how we process it, how we are permitted to process it. Huge portions of it made sense to me, but one thing that didn’t was Cooper’s discussion about how long and how severely the loss of her mother affected her as a day-to-day thing. The severity I understood, but not the length. Obviously it’s a loss that isn’t going to go away, I thought, but how could it have such an impact on your day to day life for years? Now I understand, and I wish I hadn’t had to gain that understanding the hard way. So much of what I do has my mother in it, both in the sense of her role in my development as a person, and in terms of what does and does not spark memory. I cried the first time I cooked a meal from scratch after she died. I’ve spent a lot of time being angry at nothing, and I keep having to stop myself from calling her. I can already tell you baseball season is going to be hard this year. She never did get to see a Jays game in person. It’s not clear to me that I’ll be able to read anything by Louise Penny or P.D. James for a long while—my mother and I would swap their books back and forth. She would read one of James’ novels and then pass it on to me, and I would do likewise with Lousie Penny’s. I’d brought my mother a copy of Glass Houses to read during her recovery, which came home with me unread, and now I can’t see it on my shelf or pass it in a bookstore without choking up. The last book she gave to me was Sheena Kamal’s The Lost Ones, which I now doubt I will ever read, but definitely won’t be able to part with. There are a few things of this category in my apartment right now: A beer glass she bought me for Christmas, which is a story in itself of guilt, misunderstanding, and gestures that were appreciated but unnecessary. I ate the last of the ginger candies she gave me on the eve of her surgery, and now there is some kind of pepper sauce I haven’t opened yet, the last gift of food from a mother whose identity was so wrapped up in cooking and eating that it seemed like there would be a never ending flow of it. In my freezer is a Thanksgiving dinner from 2017 that I never got around to eating and is now the last meal she cooked that still exists, beyond eating for age regardless of sentimentality, but that I can’t bring myself to get rid of yet, even though I know I already should have done so. Perhaps not the final gifts from a mother to her son, but the last tangible ones, from her hand to mine.

I’ve been thinking a lot in the last few months about things, and how they relate to our sense of self and how they allow us to externalize memory and the emotional baggage that we carry. I’ve written about this before, if only in passing, but it’s quickly approaching a crisis point in my life as I find myself not only trying to manage my own past in a living space with a partner and no storage, but my parents’ pasts as well. I suddenly have an apartment full of my mother’s things, as well as objects important to my father and stepfather—or even just things that they were ready to throw away that I feel need documenting or at the very least more serious consideration before ending up in some thrift shop or landfill. The volume of it all is as daunting as the emotional weight most of these items carry. Going through it all, making decisions and taking actions, will be work, in every sense of the word. I understand, to a point, my stepfather’s need to run from so much of this after my mother’s death, but I’m the sort of person who needs to take his time, and I feel sometimes like I’ve been denied that. I claimed so much not because I knew it to be significant, but because I didn’t know, and understand the pain that can come from snap decisions, especially when the losses are unrecoverable. I didn’t visit enough, I didn’t call enough, didn’t take enough time, and now it’s too late. I will not make the same mistakes with the disposition of the remaining tangible evidence of her time and impact on this earth. But that doesn’t make it any easier to live inside this stasis.

I have my mother’s ashes, which is something I wasn’t expecting. My stepfather found them difficult to have around, which I understand, and while it isn’t easy for me to have them in the house, I feel like I’m better equipped to cope, even if only because coping, or rather enduring, has been my primary mode as an adult. I have not been much good, in my life, at solving problems or attacking them with elbow grease or whatever, but despite a history of breakdowns and crisis moments, what I am good at is just getting through it, and if I have a greater capacity for that than my stepfather, it makes sense to me to lighten his burden.

I have my mother’s ashes, which is something I wasn’t expecting. My stepfather found them difficult to have around, which I understand, and while it isn’t easy for me to have them in the house, I feel like I’m better equipped to cope, even if only because coping, or rather enduring, has been my primary mode as an adult. I have not been much good, in my life, at solving problems or attacking them with elbow grease or whatever, but despite a history of breakdowns and crisis moments, what I am good at is just getting through it, and if I have a greater capacity for that than my stepfather, it makes sense to me to lighten his burden.

The books I did turn to in the grief of this year, first after Molly and then after my mother, have been a bit of a strange lot. On the one hand there are the things you would expect; old favourites I turn to in times when I need comfort. William Gibson’s early novels, which are reliably satisfying in their neo-noir plotting and still feel fresh, and relevant, and new after all these decades. The frothy weightlessness of John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War books, never surprising or challenging in any meaningful way, but calibrated perfectly for action-movie-style adventure without veering hard to the right like so much of that does. Michael Helm’s In the Place of Last Things, a book that lets traditional, competing notions of masculinity rest side by side with the possibilities of new paths, of reconciling with change and grief—my favourite Canadian novel. The strangeness enters by way of my other concerns, with the search for difficult pleasures, with books of feminist and postmodern theories of science fiction, with books on architectural materials and public policy around housing and bathrooms. Strangest of all was the beautiful, creaking, paranoid mess of Gravity’s Rainbow and Simon Sellars’ Applied Ballardianism. Layer upon layer, I suppose, of speculation about who we are and why we live how we do, crammed, and dense and heavy. A comforting weight, maybe. My father’s health is not good, and when my girlfriend got a cold I cried for fear she might die of something small and everyday. Anything that keeps me tethered is to be embraced.

I’ve embarked on physiotherapy, finally, for a back injury I sustained in late 2017 and which has not only caused me a great deal of pain and limited my mobility severely, but has also pinched two of my nerves to the point where most of my right thigh has been numb for nearly a year. I like my physiotherapist; her treatments are effective and she won’t lie to me about how long it will take, which is to say a very long time. Progress is slow, but visible, and it’s helped my mental state to not be in physical pain all the time—or to at least be in less physical pain all the time. I get impatient, and frustrated, and my stupidity has brought about setbacks, but if 2018 were to have any real bright lights in it, this would be one. Neither triumph nor release from pain, but perhaps the potential for relief. It should be noted that Jess has been graceful and supportive beyond all reason while my grief and other pains have made me distant, snappish, and probably a very poor partner over the last several months. I cannot fathom the trench I’d be at the bottom of right now were it not for her support.

I sold a work of fiction for the first time since 2004, when “A Story with No Title Whatever” appeared in issue 16 of Carousel—I once joked that I called it that because I was saving “Untitled” for something special. My story, “Tobacco Hand,” which I think I wrote the first draft of in 2005 or 2006, will appear in the next issue of the Dalhousie Review, on shelves sometime in February of 2019, I think. I made the sale last spring, but didn’t tell my mother. I’d been saving it as a surprise. I hope she’d have been pleased.

This year I reviewed Alex Leslie’s second book of short stories, We All Need to Eat, which I can recommend without reservation. I had hoped it would receive a starred review based on what I wrote, but that’s not up to me. Leslie is an astonishing writer, and deserves to be widely read. The Last Word, which I mentioned above, is worth your time, and so is Lezlie Lowe’s No Place to Go, the book about public bathroom policy which I alluded to. I found it to be a bit on the light side, but it’s an important public policy issue and she covers it well. I read Half the Day Is Night, by Maureen F. McHugh, an excellent book from a reliably excellent writer, although it’s only available in print-on-demand format. My copy came with a significant printing error, a big risk with print-on-demand, and Macmillan are being uncommunicative dicks about it, so my copy remains unsatisfying as an object. David Madden and Peter Marcuse’s In Defense of Housing is an incredibly important book to read if housing policy is something you’re interested in at all; it’s mostly about New York, but it has implications for every city in North America. I read some things by Takayuki Tatsumi, and if Japanese science fiction or cyberpunk are topics that interest you at all, track down anything he’s been involved in. While we’re on the subject of cyberpunk, Lewis Shiner’s Frontera seems to me an unsung classic of the genre, one I never see talked about that was far better than Bruce Sterling’s Schismatrix stuff or most of Pat Cadigan’s oeuvre, and Zachary Mason’s Void Star is a tremendous contemporary addition to the canon. My girlfriend bought me a book called Concrete Toronto: A Guide to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies, which is a beautiful and fascinating exploration of some of the city’s most interesting buildings. Carlen Lavigne’s Cyberpunk Women, Feminism and Science Fiction: A Critical Study is necessary reading for anyone who wants to think deeply about cyberpunk, despite having significant problems, including some deliberate misreadings and decontextualization. Lavigne’s book has brought a number of writers to my attention, and I’ll be tracking down their work. Four final recommendations: Bullshit Jobs, by David Graeber; Brown: What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone), by Kamal Al-Solaylee; Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan, by Jake Adelstein (which seems to be good despite Adelstein rather than because of him—he comes across as kind of an oblivious dick); and finally, Twelve-Cent Archie, by Bart Beaty, perhaps the first academic or para-academic study of everyone’s favourite teenage redhead.

This year I reviewed Alex Leslie’s second book of short stories, We All Need to Eat, which I can recommend without reservation. I had hoped it would receive a starred review based on what I wrote, but that’s not up to me. Leslie is an astonishing writer, and deserves to be widely read. The Last Word, which I mentioned above, is worth your time, and so is Lezlie Lowe’s No Place to Go, the book about public bathroom policy which I alluded to. I found it to be a bit on the light side, but it’s an important public policy issue and she covers it well. I read Half the Day Is Night, by Maureen F. McHugh, an excellent book from a reliably excellent writer, although it’s only available in print-on-demand format. My copy came with a significant printing error, a big risk with print-on-demand, and Macmillan are being uncommunicative dicks about it, so my copy remains unsatisfying as an object. David Madden and Peter Marcuse’s In Defense of Housing is an incredibly important book to read if housing policy is something you’re interested in at all; it’s mostly about New York, but it has implications for every city in North America. I read some things by Takayuki Tatsumi, and if Japanese science fiction or cyberpunk are topics that interest you at all, track down anything he’s been involved in. While we’re on the subject of cyberpunk, Lewis Shiner’s Frontera seems to me an unsung classic of the genre, one I never see talked about that was far better than Bruce Sterling’s Schismatrix stuff or most of Pat Cadigan’s oeuvre, and Zachary Mason’s Void Star is a tremendous contemporary addition to the canon. My girlfriend bought me a book called Concrete Toronto: A Guide to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies, which is a beautiful and fascinating exploration of some of the city’s most interesting buildings. Carlen Lavigne’s Cyberpunk Women, Feminism and Science Fiction: A Critical Study is necessary reading for anyone who wants to think deeply about cyberpunk, despite having significant problems, including some deliberate misreadings and decontextualization. Lavigne’s book has brought a number of writers to my attention, and I’ll be tracking down their work. Four final recommendations: Bullshit Jobs, by David Graeber; Brown: What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone), by Kamal Al-Solaylee; Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan, by Jake Adelstein (which seems to be good despite Adelstein rather than because of him—he comes across as kind of an oblivious dick); and finally, Twelve-Cent Archie, by Bart Beaty, perhaps the first academic or para-academic study of everyone’s favourite teenage redhead.

I normally end these with a promise to write more. I mean it every year, and this year is no exception, but I’m considering alternate formats. A newsletter, maybe, or Medium. We’ll see what happens.