I apologize for the lateness of this reading breakdown; I’d anticipated having time to work on it back in January, but other projects intervened over and over again, and I simply haven’t had the time until today. My reading project for 2017 was significantly smaller in scale than in previous years, and if nothing else, the sharper focus yielded fewer books I didn’t connect with—in fact, I chose not to make a “worst of the year” list at all.

I apologize for the lateness of this reading breakdown; I’d anticipated having time to work on it back in January, but other projects intervened over and over again, and I simply haven’t had the time until today. My reading project for 2017 was significantly smaller in scale than in previous years, and if nothing else, the sharper focus yielded fewer books I didn’t connect with—in fact, I chose not to make a “worst of the year” list at all.

For those who haven’t been reading along,[ref]To be fair, there probably aren’t that many of you who have been.[/ref] for Canada’s 150th birthday I read and wrote about one book every month that was new to me but is considered a Canadian classic by one metric or another. Since I finished early, I also wrote about a “bonus” thirteenth book that was recommended by several people.

I read a total of 71 books in 2017, down 22 from 93 in 2016 and down 1 from 72 in 2015. I once again did not read with issues like gender and race as any sort of focus beyond trying to provide at least some balance in my core 12 Canadian books, but I did try to be conscious of those factors. Bearing in mind that there is significant overlap between some categories, my breakdown for 2017 looks like this:

41 books/58% by men, down from 62 books/67% in 2016

30 books/42% by women, up from 27 books/29% in 2016

0 books/0% by both men and women, down from 4 books/4% in 2016

11 books/15% by people of colour, up from 7 books/8% in 2016

6 books/8% by women of colour, up from 2 books/2% in 2016

1 book/1% by Native authors, matching 2016

2 books/3% by LGBTQ authors,[ref]This is a best guess based on authors who have made public declarations about their sexual orientation. I don’t keep super close track of this statistic, as information isn’t always available and some folks would prefer to keep this aspect of their identity private, which I respect.[/ref] down from 5 books/5% in 2016

7 books/10% in translation, up from 3 books/3% in 2016

30 books/42% were Canadian, up from 19 books/20% in 2016

19 books/27% by Canadian women, up from 6 books/6% in 2016

0 books/0% by both Canadian men and women, down from 1 book/1% in 2016

4 books/6% by Canadian people of colour, up from 3 books/3% in 2016

2 books/3% by Canadian women of colour, up from 1 book/1% in 2016

1 book/1% was self-published, down from 9 books/10% in 2016

7 books/10% were non-fiction, down from 24 books/26% in 2016

32 books/45% were genre fiction, down from 53 books/57% in 2016

36 books/51% were literary fiction, up from 13 books/14% in 2016[ref]I know the genre/literary fiction numbers add up to more books than the total volumes of fiction I read in 2017, but that’s because there is overlap between the two categories.[/ref]

And now here are the best books I read in 2017, in the order I read them, not counting re-reads:

- Willem de Kooning’s Paintbrush, by Kerry Lee Powell

- The Devourers, by Indra Das

- The Tin Flute, by Gabrielle Roy

- Baseball Life Advice, by Stacey May Fowles

- Pastoral, by Andé Alexis

- China Mountain Zhang, by Maureen F. McHugh

- Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life, by Adam Greenfield

- Storming the Reality Studio: A Casebook of Cyberpunk & Postmodern Science Fiction, edited by Larry McCaffery

- The Diviners, by Margaret Laurence

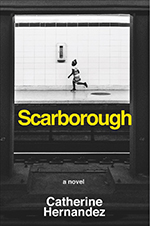

- Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez

- Two Travelers, by Sarah Tolmie

- Satin Island, by Tom McCarthy

- The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, by Thomas King

There is no “worst” list this year, so here are the honourable mentions:

- As for Me and My House, by Sinclair Ross

- Wolf in White Van, by John Darnielle

- Chalk, by Paul Cornell

- Bear, by Marian Engel

I noticed something interesting as I was reading through these classic Canadian books, almost all of which were novels: there seemed to be thematic clusters that developed over time. I don’t want to say that these 13 books were somehow representative of all Canadian literature; that certainly isn’t the case. But as a for instance: the vast majority of the work published prior to the late 1960s was very heavily concerned with class, even when other major themes were present. Virtually none of the writers seemed to assume a middle class “we” in terms of either subject, readership, or where artistic sympathy would settle. The middle class weren’t excluded, by any means, but they were one class among many, and often treated as though they were as strange and alien as the very rich. The rural/urban divide is also especially strong in these early works. Issues around gender show up as as a thematic concerns in many of the early books I read, but seldom as the primary concern, and almost always linked to class. Class gradually took a back seat to gender issues the closer the books got to the modern era. It was still present, of course, particularly in the work of Margaret Laurence[ref]A writer whose work is criminally under-valued, in my opinion.[/ref] and Alice Munro, but by the time I got to The Handmaid’s Tale the tone of the work very clearly implied both a middle class reader and subject. CanLit was no longer about the poor at all, and it certainly didn’t seem to be for the poor in any meaningful sense. The most modern Canadian books I read, however, were deeply concerned with race, a subject that had been far too long neglected, although Margaret Laurence certainly made good efforts to acknowledge it as a factor in the lives of some of her characters, and linked it rather directly to class. Only two writers, Austin Clarke and Margaret Laurence, seemed able to integrate race, gender, and class into a single book, and I wouldn’t say either of them did so with complete success, though I think Laurence did a slightly better job.

I noticed something interesting as I was reading through these classic Canadian books, almost all of which were novels: there seemed to be thematic clusters that developed over time. I don’t want to say that these 13 books were somehow representative of all Canadian literature; that certainly isn’t the case. But as a for instance: the vast majority of the work published prior to the late 1960s was very heavily concerned with class, even when other major themes were present. Virtually none of the writers seemed to assume a middle class “we” in terms of either subject, readership, or where artistic sympathy would settle. The middle class weren’t excluded, by any means, but they were one class among many, and often treated as though they were as strange and alien as the very rich. The rural/urban divide is also especially strong in these early works. Issues around gender show up as as a thematic concerns in many of the early books I read, but seldom as the primary concern, and almost always linked to class. Class gradually took a back seat to gender issues the closer the books got to the modern era. It was still present, of course, particularly in the work of Margaret Laurence[ref]A writer whose work is criminally under-valued, in my opinion.[/ref] and Alice Munro, but by the time I got to The Handmaid’s Tale the tone of the work very clearly implied both a middle class reader and subject. CanLit was no longer about the poor at all, and it certainly didn’t seem to be for the poor in any meaningful sense. The most modern Canadian books I read, however, were deeply concerned with race, a subject that had been far too long neglected, although Margaret Laurence certainly made good efforts to acknowledge it as a factor in the lives of some of her characters, and linked it rather directly to class. Only two writers, Austin Clarke and Margaret Laurence, seemed able to integrate race, gender, and class into a single book, and I wouldn’t say either of them did so with complete success, though I think Laurence did a slightly better job.

Perhaps the best Canadian book I read all year wasn’t even part of my reading project, and has not been around long enough to be considered an acknowledged classic, although I hope it one day will be. Catherine Hernandez’ Scarborough took a truly intersectional approach to all the issues the Canadian writers in my project had addressed in piecemeal fashion, not prioritizing one thing over another, but refusing to give any of them short shrift. She rekindled CanLit’s ancient empathy for the poor, looked gender inequality in the eye, wrestled with the problems of racialized communities within Canada, both Native and immigrant, and refused to pretend that full equality for LGBTQ Canadians is somehow a solved problem—in a sense, Scarborough tries to deal with nearly all the themes classic Canadian books tackled, and did so with a strength and richness that equals the best of them. I hope other Canadian writers out there are taking note; I have read many excellent Canadian novels over the last few years, but Catherine Hernandez has given us a book that is important, not only as a piece of art, but as a wake-up call—we need not feel ourselves latecomers. We have not solved the problems earlier writers were concerned with, either socially or artistically, but nor are we bound by their forms: we can create art that is true to who we are today, as fragmented and contingent and intersectional as that may be, without giving up on that work.

There are two other books I want to mention briefly before closing. The first is The Devourers, by Indra Das. It’s a fantasy novel about werewolves, which I know may make some of you disinclined to read it; I beg you to reconsider. Das’ prose is strikingly beautiful, and the book has an emotional depth that truly took me by surprise. The second is Radical Technologies, by Adam Greenfield. Adam is a friend of mine in that distant online way, and he writes so lucidly about the social ramifications of technology that I feel it is in every responsible citizen’s best interest to read his book, wether or not technology is a subject that interests them. It offers important and urgent insights into how our world is changing, so much so that were it in my power to assign reading to anyone, Radical Technologies would be the first title on the list.

There are two other books I want to mention briefly before closing. The first is The Devourers, by Indra Das. It’s a fantasy novel about werewolves, which I know may make some of you disinclined to read it; I beg you to reconsider. Das’ prose is strikingly beautiful, and the book has an emotional depth that truly took me by surprise. The second is Radical Technologies, by Adam Greenfield. Adam is a friend of mine in that distant online way, and he writes so lucidly about the social ramifications of technology that I feel it is in every responsible citizen’s best interest to read his book, wether or not technology is a subject that interests them. It offers important and urgent insights into how our world is changing, so much so that were it in my power to assign reading to anyone, Radical Technologies would be the first title on the list.

My reading project for 2018 is already well underway; I have decided to read books of theory[ref]With as broad a definition of that term as possible.[/ref] in 2018, and to that end I’ve already finished Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics by Laura Kurgan, Brown: What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone), by Kamal Al-Solaylee, and Four Futures: Life After Capitalism by Peter Frase—and I’m currently reading Takayuki Tatsumi’s Full Metal Apache: Transactions Between Cyberpunk Japan and Avant-Pop America.