The Kansas City Royals are visiting Toronto, and it’s the top of the fifth inning. Danny Duffy’s heavily-pixelated face fills the screen of my 49″ 4K Sony Bravia, but he’s not on the mound tonight. He’s got a headset on, and he’s trading stories back and forth with Scott Braun, Cliff Floyd, and Jeremy Guthrie, sometimes answering questions but mostly just shooting the breeze. I’m a Blue Jays fan, but I’ve never been good at internalizing information about other teams, so I rely pretty heavily on Buck Martinez and Pat Tabler to fill in the blanks for me during a game. What’s this guy usually like at the plate? Is this other guy a strong shortstop, or has he been struggling with injuries? Right now, Danny Duffy is the only one who seems interested in calling the game, commenting on the plays he can see from the dugout. The interview, which eventually becomes picture-in-picture so I can actually see what’s happening on the field, lasts for half of a blurry, low-resolution inning. They talk about Robin Thicke and Avril Lavigne.

This might not be the worst thing about watching a ballgame on Facebook, but it’s in the running.

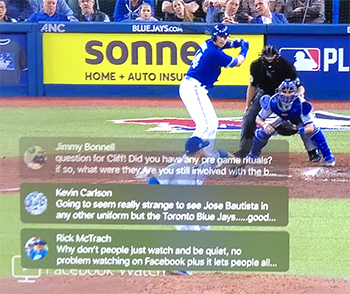

Facebook comments block the view of home plate.

Facebook as a platform is itself problematic, to put it mildly. For years they’ve been Uber’s chief competitor for the title of most transparently corrupt and abusive tech company in North America, and to say that I was reluctant to install their app on yet another device is an understatement. Each of us draws our own line on these things; I still feel like I get some value from Facebook, but the returns are starting to diminish rapidly.

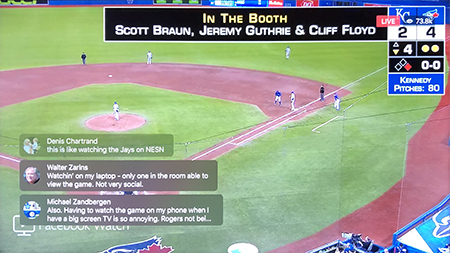

On-screen graphics, minus reaction icons.

I filled out an MLB “fan feedback” form earlier today, expressing how irritating I found the idea of this game being Facebook exclusive, rather than simply making Facebook one option among many. I explained that given the current news I found Facebook a less than ideal partner for this kind of venture, and that I had very real concerns. They responded quickly with what felt like a deliberate misreading of my concerns: if I don’t have a Facebook account, they said, I can always listen to the game on the radio, or watch the archived version that will be available on MLB.tv 90 minutes after the end of the game. I was tempted to respond with a hearty “go fuck yourself,” given that’s basically what they had said to me, but I wasn’t even sure their email had been from a real person. It had the stink of automation on it. But then, even it had been from a real person, it wouldn’t have been from a person who could do anything about it. It’s unlikely anyone who matters will ever see or hear my feedback.

That brings me to one of the biggest problems with broadcasting games exclusively on Facebook: it’s supposed to be about bringing in more new viewers, but it misunderstands what’s alienating potential fans in the first place. I was a ball player in high school. Right field, and then third base. I was never any good, but it was fun. I followed the Jays, collected the cards, had a cap and a silky, pale-blue pitcher’s jacket. I couldn’t tell you why I walked away from the game, but I did, and for nearly twenty years. It was the Internet that brought me back. More specifically, it was the smart, enthusiastic commentary from the kind of voices who have traditionally been shut out from professional sports—in particular, the work of novelist-turned-sportswriter Stacey May Fowles. The Internet has a lot of offer Major League Baseball.

There are so many things that alienate potential fans. Not making newcomers feel welcome in sports communities, online or off. Clinging to toxic, outdated ideas about who sports are for and what acceptable behaviour in sporting circles looks like. Streaming games on Facebook isn’t really going to fix any of those things, and I don’t think it was meant to. But there is one lower-stakes thing alienating fans that Facebook streaming could address: blackouts.

Facebook reaction icons.

Honestly, though, none of that was the worst part of tonight’s game. I don’t remember now if I first tuned in during the third or the fourth inning, but when I did, Scott Braun, Cliff Floyd, and Jeremy Guthrie were having an extended conversation about the Yankees and the Red Sox and were mostly ignoring what was happening in the game they were supposed to be calling. And that was how they called most of the game: by ignoring it. They seemed to be having a good time, but there was never a sense that they were invested in either team, they weren’t intimate with either ball club’s personalities and foibles, and they seemed more interested in the novelty of Facebook than in helping fans get the most from the game, which is ultimately their job. They didn’t seem to care, and it made it harder for me to care. That, finally, was the worst part of watching a game on Facebook: everyone involved seemed so caught up in the technology that they forgot to care about the baseball.