Ahoy! This is the Weekly Churn, where every Sunday I post about what I’ve been reading, watching, and thinking about over the previous week.

I spent a lot of nights watching television when my mom died. I didn’t have the headspace to read, and while getting shitfaced was helpful a couple of times, I didn’t want it to become a habit. When I was in my early 20s I had what used to be called a “nervous breakdown” and was depressed and more or less non-functional for the better part of a summer. During that period I found that the only thing I could really handle was gentle, optimistic movies and television. I watched a lot of Disney, much to the irritation of my girlfriend. I won’t credit that kind of thing with bringing me out of my depression, but it did prevent me from sinking any lower. Last September I found something just as good: Forged in Fire.

If you’re not familiar with Forged in Fire, it’s a lot like the cooking show Chopped, except instead of making dinner they make knives. The show starts with four bladesmiths in a studio. In the first round they are told to forge a blade in three hours, within certain parameters supplied by the judges. Sometimes they’re asked to make a signature blade in their signature style, and other times they’re asked to make a specific style of knife, like a trench knife or a kukri. The steel and most of the tools are provided, although sometimes the steel is a cylinder or a ball-bearing, sometimes the smiths need to salvage it from a vehicle or from around a junkyard. Other times they are asked to make Damascus steel (several hardenable steels blended together in layers or patterns) or use a san mai technique (hardenable steel sandwiched between two layers of mild steel, with the hard steel exposed at the blade’s edge). The smith with the least successful blade is eliminated at the end of the round. In the second round the smiths are asked to build a handle for their knives, again following certain parameters. At the end of that round the judges put the knives through truly brutal strength and sharpness tests (antler chops, seatbelt slices), and the smith whose knife is least successful goes home. The remaining two smiths are sent back to their home forges and given five days to build a large, complex edged weapon from scratch. At the end of those five days their weapons are tested in strength, sharpness, and kill tests (the latter usually performed against a ballistics dummy or some kind of animal carcass).

Sounds brutal, right? Except… it’s not. It’s a really soothing, almost meditative show. It was on the History Channel almost every night last September, and I watched as much of it as I could find. J watched it with me, and we’ve since become kind of obsessed. There’s so much about Forged in Fire that breaks down and reworks the premise of reality television competitions. The judges are quirky, to say the least, but they come from backgrounds where teamwork and craftsmanship are more important than ego, and where being an asshole isn’t rewarded with celebrity the same way it is with television chefs. In fact, being a hyper-competitive asshole is actively discouraged on Forged in Fire, and is the sort of thing that works against competitors.

Almost all the competitors are men, and they came to forging in a bunch of different ways. Some of them learned the craft from their fathers; some came to it from a desire to do something with their hands that feels traditionally masculine but that requires focus, discipline, and knowledge as much as brute strength; still others came to it because they love fantasy literature or history. A lot of the competitors are former military servicemen, and while it’s almost never said out loud, forging knives has become a way of working through pain for a lot of them, a way of taking their hurt and doing something with it that’s creative instead of destructive. It feels like “PTSD” is the elephant in the room in more than a few episodes.

Other people have written about the show’s relationship to masculinity. And there have been women who have won—J and I cheered when Kelly Vermeer-Vella won for a truly amazing falcata, although the judges may have been more pleased about her being a farrier than about being the first woman champion (the judges often celebrate farriers as a profession for their speed, skill, and overall dedication to craft).

But there isn’t just the elephant in the room: what’s also in the room is camaraderie. Contestants help each other, cheer each other on, commiserate with genuine empathy when something goes wrong. The show likes to highlight friendships, professionalism, good cheer, and taking pride in a job well done. On the rare occasion when a blade goes so horribly wrong that a competitor turns in little more than a misshapen lump of steel, the only thing that matters to anybody else in the room is “did they keep trying?” As long as the answer is “yes,” the judges make sure the contestant leaves knowing that, even though they didn’t win, they aren’t going home a failure.

Since my mother died the show has offered me a space where I can laugh, and be calm, and see stories of real people working through things without it being about anger or about false stoicism. It’s about the work, and about how when things go wrong, putting in work can get you through.

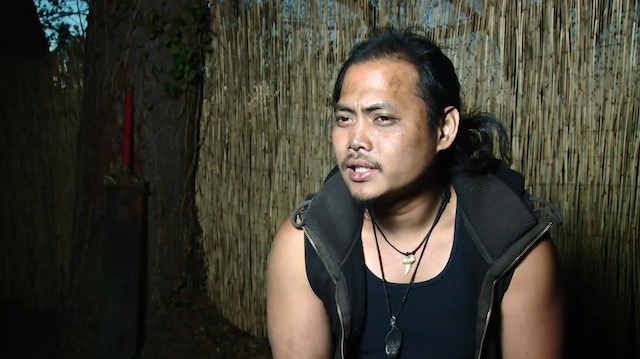

Of course, J and I have our favourite competitors, and competitors we dislike. There was a white guy named David Goldberg in season one who insisted on building his entire forging practice around Japanese methods and spirituality to the point where it was making us more than a little uncomfortable (and the fact that he was good just made it worse). But nobody will ever top Ryu Lim, a Filipino smith dedicated to tradition and primitivist aesthetics who is also just comically badass.

We still talk about Ryu Lim’s episodes. He won the title of Forged in Fire Champion in the third episode of the first season by forging a viking battle axe in a home forge that was made from a cast iron frying pan, a satellite dish, and a hair dryer. In season three he returned for a fan favourites episode, but was sadly eliminated in the first round. In his introductory interview at the start of the episode he confided that the shark tooth in his necklace came from a shark he killed in single combat using one of the knives he’d forged in his frying-pan-and-hair-dryer contraption. We need more Ryu.

I don’t want to say that this show “got me through” some hard times, because that’s a bit of an overstatement, but when we watched the most recent episode last night I thought about how I got hooked on the show, and about how the first anniversary of Molly’s death is just around the corner, and the first anniversary of my mother’s not long after, and I’m glad that things like this are out there, and glad I was able to find it.

Anyway, that’s all for this week. Thanks for reading!