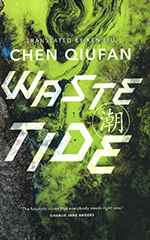

This was one of those instances where it was ultimately the cover that brought me to the book. Quite often with science fiction and fantasy I’m reading a book despite its cover, rather than because of it. With a few exceptions—what Gollancz did for Simon Ings, Infinite Detail, some Samuel R. Delany re-issues, and a few editions of some of William Gibson’s books—I find the cover art chosen for science fiction and fantasy titles to be grossly lacking any kind of mature design sensibility. Very often we find ourselves not far off from Boris Vallejo wannabes airbrushed onto the side of a Ford Econoline. The original English-language cover for Waste Tide featured a competent painting of two people examining an abandoned mech with a flashlight. It’s a reasonably accurate depiction of a significant plot point, but tonally inappropriate and ultimately disappears on the shelf next to dozens of similar painted covers. The English-language trade paperback cover is much more striking. It features a vivid photograph by Michael Milner, reminiscent of Edward Burtynsky’s Anthropocene Project, that not only stands out from other science fiction titles on the shelf, but also provides a brutally accurate visual reference for the novel’s setting that actually aligns with the novel’s tone. The type treatment is appallingly bad, but I suppose we can’t have everything.

This was one of those instances where it was ultimately the cover that brought me to the book. Quite often with science fiction and fantasy I’m reading a book despite its cover, rather than because of it. With a few exceptions—what Gollancz did for Simon Ings, Infinite Detail, some Samuel R. Delany re-issues, and a few editions of some of William Gibson’s books—I find the cover art chosen for science fiction and fantasy titles to be grossly lacking any kind of mature design sensibility. Very often we find ourselves not far off from Boris Vallejo wannabes airbrushed onto the side of a Ford Econoline. The original English-language cover for Waste Tide featured a competent painting of two people examining an abandoned mech with a flashlight. It’s a reasonably accurate depiction of a significant plot point, but tonally inappropriate and ultimately disappears on the shelf next to dozens of similar painted covers. The English-language trade paperback cover is much more striking. It features a vivid photograph by Michael Milner, reminiscent of Edward Burtynsky’s Anthropocene Project, that not only stands out from other science fiction titles on the shelf, but also provides a brutally accurate visual reference for the novel’s setting that actually aligns with the novel’s tone. The type treatment is appallingly bad, but I suppose we can’t have everything.

Waste Tide‘s premise is something that attracted me right away: it’s about people who live or work on “Silicon Isle,” an island off the coast of China where most of the workers are trapped in poverty and make their living processing electronic waste generated primarily by wealthy Western nations, and about the various power struggles and structures of oppression that are keeping them in poverty and destroying their home. The novel has several different point of view characters; Scott Brandle, the self-described economic hit man on the island to secure a contract for a large recycling firm; Chen Kaizong, the translator from America who was born on the island; Mimi, one of the so-called “waste people” who came to the island to work in the e-waste recycling plants; and to a lesser extent, Luo Jincheng, who is one of the traditional clan leaders of the island’s native population. These characters dance around each other and the power relationships and culture clashes that govern life on the island, sometimes searching for the main chance, sometimes just looking to survive, or to self-destruct. Those relationships all come crashing down when a piece of experimental technology is found in a shipment of waste, and life on the island becomes significantly more dangerous.

This should have been right up my alley, as the intersection of class dynamics and the politics of our technological landscape fascinate me, but I found that Waste Tide didn’t quite land for me. The setting is great, and the characters are interesting, but Chen just never went far enough with it for me. First, nearly every character we meet in the novel is there because of their job, because of labour forces, but unlike in, say, a William Gibson novel, we almost never actually see any of these characters working. A novel where one of the main drivers of the plot is labour politics fails rather mightily to depict any actual labour. We see Mimi working for the span of about three pages, and Kaizong does about half a day of translating for Scott before he’s replaced. Scott and Jincheng do the most “work,” although it basically amounts to taking meetings and issuing orders. For a novel where the plot hinges so heavily on labour politics, it seems awfully scared of depicting any actual labour. I was expecting something much more like Maureen F. McHugh’s “Special Economics,” from After the Apocalypse.

I know that it can seem like work is boring, and that it can drag a book down if it’s not handled well, but that’s a reason to handle it well, not to avoid it. Virtual Light features more pages of its characters working than Waste Tide, and labour is much less central to that novel. Likewise any of Malka Older’s Centenal Cycle books. The ecological catastrophe the waste recycling industry has wrought on Silicon Isle, the other great motivating force in the novel, is given significantly more attention than labour, but still feels like it was played for flavour much of the time. It’s a fine balance to maintain, and I don’t think Chen was entirely successful. Most of Waste Tide’s early chapters pointed to a much more procedurally-focused novel, but eventually the typical science fiction plot beats took hold, and after a slow but solid start it began its march to the inevitable violent confrontation that would resolve all the hanging plot threads. Just another writer with a good idea trapped by their genre rather than freed by it.

I want to touch briefly on Ken Liu’s translation work. For the most part I found it quite good, or at least invisible, which is what I mostly want. I would have easily believed Waste Tide was an English-language original, were it not for a few small things. Liu’s introduction makes clear how complex a work this was to translate, and why he used certain terms over others, and why he did things like provide certain tone marks in footnotes. The tone marks were distracting at times, but there’s not much to be done about that, especially when a translator is working in a context where multiple languages are in play, and must make moves to indicate how they relate to each other. Liu’s choice to use the term “bitrate” instead of “bandwidth” was pretty confusing. Network traffic is heavily limited on Silicon Isle, and Liu chose the term “bitrate” to describe that network traffic. Typically, that term is used either to describe the quality of compressed information, or the transfer rate from one specific node in the network to another. “Bandwidth,” on the other hand, is generally used to describe how much information the node can handle at once from all connections, not just one-to-one. In the context of the novel, Liu’s deployment of “bitrate” was much closer to the common usage of “bandwidth.” It was a bit like a grain of sand in your food; unlikely to do any damage, but super annoying. The only other thing that brought me out of it was his translation of certain quotations from other languages. He chose to leave certain phrases untranslated from Italian, which was frustrating, because those phrases have very famous (public domain!) English translations that would have been instantly recognizable to most Anglophone readers. He also chose translations for famous biblical quotations that were more modern than the most well-known English-language translations, and flowed less smoothly. In both instances it was like coming across something familiar that was rendered uncanny in some way; not quite right.

Waste Tide is certainly worthwhile, and it’s the only science fiction novel I’ve encountered so far that tackles the intersection of labour and technological waste so directly, but it never seemed to come together in a satisfying way, dropping deeper explorations of its themes in favour of generic science fiction plot beats.